Anna (Hannah) Moiseevna Smushkevich

Anna (Hannah) Moiseevna Smushkevich, daughter of Moisei (Moisha) Aronovich Smushkevich and Haya (Chaya, Khaya) Abramovna Smushkevich, was born on 10 Mar 1902 in Lubni, Ukraine and died on 19 Jun 1964 in Kiev at age 62.

Anna married Yefim Abramovich Sorokin.

These memories were written by her daughter Zinaida Yefimovna Sorokina.

My mother, Anna Moiseevna Sorokina (Smushkevich by birth), was born in 1902 on the Jewish holiday of Purim on the 10th of March. She was born in the city of Lubni in the Poltava region. She was given a Jewish name Hannah, but only her parents called her by that name; her brothers, sisters, nephews and friends called her Anna, Aunt Anna and Anna Moiseevna.

Mom finished primary school that was organized and run by a local church in Lubni. She was a very good student in all subjects and had nice handwriting. Even the priest who taught “God’s Law” (everyone had to take this class, regardless of their religion) praised her as an exemplary student in front of the whole class. Mom loved learning and wanted to continue to study, but her parents decided that for raising children and maintaining a household her education was adequate. Mom read a lot and purchased new books for us.

At eighteen years of age she was given in marriage; dad was twenty five years old at the time. Before this he fought in the First World War and was taken prisoner in Austria-Hungary. Father was a modest, quiet, intelligent and handsome young man. Mom was also intelligent but she was also more energetic and because of that she was the head of the family. Dad always supported Mom in everything. They were both kind people and were loved by all.

In 1930 we moved from Lubni to Kharkov. At that time, Kharkov was the capital of the Ukraine

This was a difficult time in the Ukraine: hunger was rampant. People were dying from hunger. I remember in Poltava, people were lying on the streets, their bodies swollen from hunger. They were already dead. That year, my mother sent me and [my sister] Rita to our grandmother in Poltava and found employment for herself, because dad’s income alone was not enough.

Our parents sent us foodstuffs from Kharkov, which were lacking in Poltava. I remember one of the times when mom sent us bread products Rita and I grabbed a loaf each and devoured it as if it were the tastiest pastry in the world. In Poltava at that time bread rations were given out to those who held special permits. This bread was very dark and not appealing. Uncle Yasha and I (he was thirteen years old at the time, I was seven) went to the store to get this bread and carried it home very carefully, so that not a single crumb was lost.

Slowly life was getting back to normal. We returned to Kharkov, went to school, our parents bought a piano and sent us to learn how to play it. At first we learned at home, with music teachers who came over. Initially our music teacher was Muza Yakovlena; she was very overweight and was in love with music and used to take us to symphony concerts. The one concert I remember most was the waltz of Strauss. Afterwards we were instructed how to play piano by a male teacher. He was a composer in the theater “The Young Audience Member,” where mom worked at the time. Then we went to music school, where in addition to music we were also taught ballet. Further instruction was interrupted by war.

The 22nd of June, 1941 marked the beginning of the Second World War with fascist Germany. Kharkov was not yet occupied by Nazis but it was air bombed every day and night. In the evenings it was very dark, the streetlights were not lit, the house windows were covered by dark drapes so that no light would be visible outside. Furthermore the glass in the windows was covered with paper tape, so that it would not shatter during the bombings.

I remember the first air raid. Mom, Rita and I were coming back home from visiting guests. We were going by tram. Suddenly the sound of many explosions filled the air and shattered glass was falling on the tram. People were running out of the tram and hiding in random houses that were nearby. In the backyard we dug bomb shelters which were these earth ditches. That was where we hid when the bomb warning alarm was sounded.

In the fall we evacuated from Kharkov to the Urals. We went in a refrigerated car (intended for the transport of frozen products and ice-cream). The car was large but without windows. We were two families in the car; mom with us and another four-person family. Our dad stayed behind in Kharkov and was planning to evacuate with his tractor factory at a later time. For the most part we remained laying down because it was impossible to sit or stand up. We were bombed along the way and when that occurred we hid under the car. Our original destination was Stalingrad, but when we got there, we were warned that to remain in Stalingrad was dangerous and that the city’s locals were leaving their city. We got on a steamship and went up the River Volga, then up Kama to the city Perm [pronounced with a soft R].

Boarding the steamship was a horrible experience; people were shoving, wanting to get into the ship as soon as possible. Baggage, even people were falling overboard into the water. But somehow, we managed to get inside. We settled in near the machinery section surrounded by loud thumps that came from the working motors. But we were satisfied even with this; there was no reason even to think about going to a cabin because they were so crowded that there was no place for an apple to fall.

In Perm we met our Aunt Raya with little Tolik [Anatoly], who was three years old. He got very sick and was put in a hospital. We waited until he got better so that we could continue our journey together.

We settled in an evacupunct, a type of “hotel” for refugees which consisted of a big hall will numerous beds where people could take turns resting. The bed sheets were never changed and people slept clothed. The beds were infested with lice which spread infection. To avoid an epidemic the evacupuncts had special sanitation stations (Sanpropusniki) where clothing was disinfected by being heated up in high-temperature dryers, while at the same time we could shower and then put on our fried clothing.

When Tolik got better we all started heading for the Urals to the city of Lower Tagil because it was the planed evacuation destination of the Kharkov Tractor Factory # 183, with which our dad was supposed to relocate to Lower Tagil. The factory would be used to produce tanks instead of tractors during the time of war.

In Lower Tagil there were a lot of people from Kharkov including our relatives: Uncle Israel with his family, Aunt Rosa, Uncle Fima and his brother Yasha and their mother. However, we did not meet Aunt Rosa and Uncle Fima, because by the time we got there, they had left for the city of Fergan in the Tashkent area of Uzbekistan. Everyone stopped in Lower Tagil and worked. Initially Aunt Raya and Tolik stayed with her husband’s relatives, and we (mom and Rita and I) rented an apartment from a landlady that lived across from the relatives. It was a section of a large room with two beds, separated by a curtain from the rest of the big room. Mom gave up one bed to Aunt Fanya (Uncle Abrasha’s wife) and her child and the three of us slept in the other bed. The child caught pneumonia and died at home shortly after the hospital and Aunt Fanya went to the frontlines to be with Uncle Abrasha.

This was a hungry time and the availability of foodstuffs in stores was scarce. Aunt Raya sometimes brought us a couple of potatoes and a small piece of butter so that we would make soup. Later mom went to the village and traded things, which we brought with us from Kharkov for potatoes. Mom would walk from one house to another in the village and would offer the items, which was unpleasant. We had to find work in a factory in order to receive ration coupons for bread and other food items. We moved from a private apartment in the city to the factory neighborhood ТЭЦ [pronounced TETS]. We were allotted a room in a barrack. The barrack was a long wooden construction with a multitude of separate rooms without any facilities; water and the toilet were outdoors.

Dad came from Kharkov six months after us and moved in to the same barrack as us. There were six of us living in one room: mom, dad, Rita and myself and Aunt Raya with Tolik. Later Raya was allotted a separate room in another barrack. And after Arkadiy and I got married we also moved into a separate room, but spent most of the time in my parent’s room. Life was slowly getting better. We all went to work at the factory. Dad worked at the relocated factory #183, and Rita and I worked in the Moscow factory #120. Initially we worked in the metallurgy department as students. I had completed tenth grades and Rita had completed ninth. Then, I transferred to work in the construction sector manually making copies of designs. And then I designed specifications for replacement plane parts. Rita went on to tenth grade. Mom worked as the director of the cafeteria in the military sector and then as a store director. We started receiving produce and bread coupons. Life became better, and it became more fun to live.

In 1943 a government edict gave permission to release factory workers to receive a higher education. (The country was in need of specialists.) I began attending the machine-building institute in Lower Tagil and specialized in metallurgy. This was the only institute in the city and even this one was relocated (evacuated) from the Ukraine. I studied there for two years, 1943-1944.

On the 9th of May, 1945 the war with Germany came to an end. I wanted to leave for Kiev but the University wanted for me to remain in Lower Tagil and complete the last two years and did not want to grant her permission to leave. (I could have left without permission but would not have been granted credit for the two years of study that I had already completed at the university. Arkadiy told my university that as a military man he was being transferred to Kiev and that as his wife I would have to go with him. The university had no choice and granted me permission to leave. Eventually, we all moved to Kiev. At first Rita and I went, because we were in a hurry to make it in time for the beginning of the new academic year in order to continue our education in Kiev. Then after a few months, mom and dad came too. I started attending the Kiev Institute of light manufacturing as a third-year; because I passed the exams for the first two years at the previous university I was accepted to the third year.

Rita continued her studies at the jurisprudence faculty in the National University of Kiev. Dad went to work, mom stayed at home. Mom was the kindest person. She helped everyone whenever she could however she could. Even now, after decades have passed I remember my mother. Mura Jerebchevskaya, our relative, says “If it weren’t for your mother I would have starved to death in the years of the war.” Another relative, Boris Zusman, who currently lives in New York, remembers the delicious venigret (beet salad) that my mother used to make. These were still difficult post-war years. The venigret salad at that time was considered a delicacy, as the Olivye salad was considered later.

My parents were very hospitable people. Our relatives from Kharkov and Lugansk often came to visit us. My parents were always happy to receive visitors. Arkadiy was always amazed how mom was able to feed not only our family but all the guests who frequented our home. The post-war period was still very difficult and hungry. Even after Rita and I lived apart from mom, Rita had her own apartment and I moved to the Far East with Arkadiy, our friends and acquaintances would still come to my mom and share their joys and sorrows, to listen to her advice and sympathy. When Arkadiy brought his mother, who had cancer, to Kiev from Lower Tagil, hoping that they would be able to find treatment in Kiev, my mom set up a separate room for her in her own bedroom, while the whole family of five people slept together in the other room. Then another member was added to the family when little Michael was born. We lived like this for a few months. Sadly, Arkadiy’s mother passed away in 1947. Dad helped Arkadiy bury her at a Jewish cemetery on Kurenevka in Kiev. She was 62 years old.

Mother loved her sons-in-law and they loved her. She adored her grandchildren and they loved her. When we left for the Far East little Michael (he was only 3 years old) was crying and wanted to stay with his grandmother. Thanks to mom I was able finish college. She helped me raise and take care of her first grandchild. Mom-grandma was only 44 years old. I already mentioned how kind my mother’s soul was.

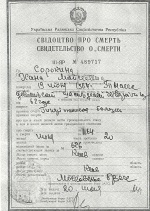

To our common grief our beloved mother, who had done so much good to many people, passed away young, at the age of 62 on the 19th of June, 1964 from complications of diabetes. Dad passed away in 1979; he was 84 years old. They were buried in the Baykovoye cemetery in Kiev. Mom and dad had lived together for 45 years in love and happiness. Even now we miss them very much.